Nature Scientific Data publishes LuwianSiteAtlas

Nature Scientific Data has published the LuwianSiteAtlas – a new, freely accessible dataset documenting 483 archaeological sites from the Middle and Late Bronze Age (2000–1200

The Luwian culture thrived in the Late Bronze Age along the Aegean’s eastern shores, near Troy. Far more than intermediaries between Mycenaeans and Hittites, they had their own language, script, and beliefs, shaping cultural exchanges that defined the ancient world.

The Luwians lived at the crossroads of the Aegean and Near Eastern worlds. Preserving writing through the Dark Ages, their thriving settlements endured for millennia, leaving a lasting legacy that deepens our understanding of the Bronze Age.

Luwian reliefs with banquet scene, food carriers and musicians in the right chamber of the south gate of Karatepe-Aslantaş, the Luwian citadel near Osmaniye in southern Türkiye (© Luwian Studies #0246)

Western Asia Minor was once home to a great culture yet to be fully recognized by archaeology: the Luwians. They lived along the eastern Aegean, opposite Mycenaean Greece, in a region the size of modern Great Britain, often contending with the Hittite kingdom to the east. Today, nearly 500 extensive settlements have been identified in Luwian lands – many still awaiting exploration.

The Luwians shaped the cultural and political dynamics of their time. Their hieroglyphic script predates the Mycenaean Linear B by centuries. Studying the Luwians sheds light on enduring mysteries of Mediterranean archaeology, including the questions about the origins of the Sea Peoples and the historicity of the Trojan War. Understanding Luwian culture is key to contextualizing these events and explaining the sudden collapse of Bronze Age kingdoms.

From the Middle and Late Bronze Age, 483 major settlement sites are known in the Luwian countries. The settlement density was at least as high as in Mycenaean Greece, Hittite Central Anatolia and Minoan Crete.

The Luwian territory covered an area of around 250,000 square kilometers, making it larger than the Hittite kingdom, the Mycenaean petty states and Minoan Crete combined.

The Luwian hieroglyphic script was in continuous use for over 1,000 years. Akkadian cuneiform was used in Hittite Anatolia for 500 years, while Minoan Crete employed three scripts over 350 years. Linear B in Mycenaean states lasted only 250 years.

Around 700 BCE, the Luwian hieroglyphic script was replaced by the alphabet. The Luwian culture persisted until the sixth century BCE, when it faded following the rise of the Persian Empire.

The Luwians, a powerful yet often overlooked civilization of the Bronze Age, bridged the cultural and political gaps between the Mycenaeans, Hittites, and later Greek societies. Archaeological discoveries of immense settlement sites, rich ore deposits, and advanced metallurgical practices reveal their mastery over the region’s resources and their influence on the Mediterranean world.

Historical accounts from ancient writers like Herodotus and Plato further highlight the wealth and sophistication of western Anatolia, pointing to the existence of an organized and prosperous Luwian society. Their legacy not only provides context for key events like the Trojan War but also explains the intellectual leaps of early Greek thinkers and the rise of Anatolian powers such as the Phrygians and Lydians.

By piecing together their contributions, we uncover how the Luwians shaped trade, culture, and innovation during a transformative era in history. Exploring their story invites us to rethink the connections between these ancient civilizations and the foundations of the modern Mediterranean.

Acknowledging Luwian states as a political and military force clarifies the collapse of the Hittite kingdom and the wider upheavals that marked the dramatic end of the Bronze Age.

Herodotus and Plato described the wealth and sophistication of the western Anatolian kingdoms, strong evidence for an organized, prosperous administration – most likely Luwian in origin.

Nature Scientific Data has published the LuwianSiteAtlas – a new, freely accessible dataset documenting 483 archaeological sites from the Middle and Late Bronze Age (2000–1200

On April 23, 2025, archaeologist and geologist Eberhard Zangger delivered a lecture in Zurich to alumni of Harvard, Stanford, Cambridge, Oxford, Yale, and Princeton, upon

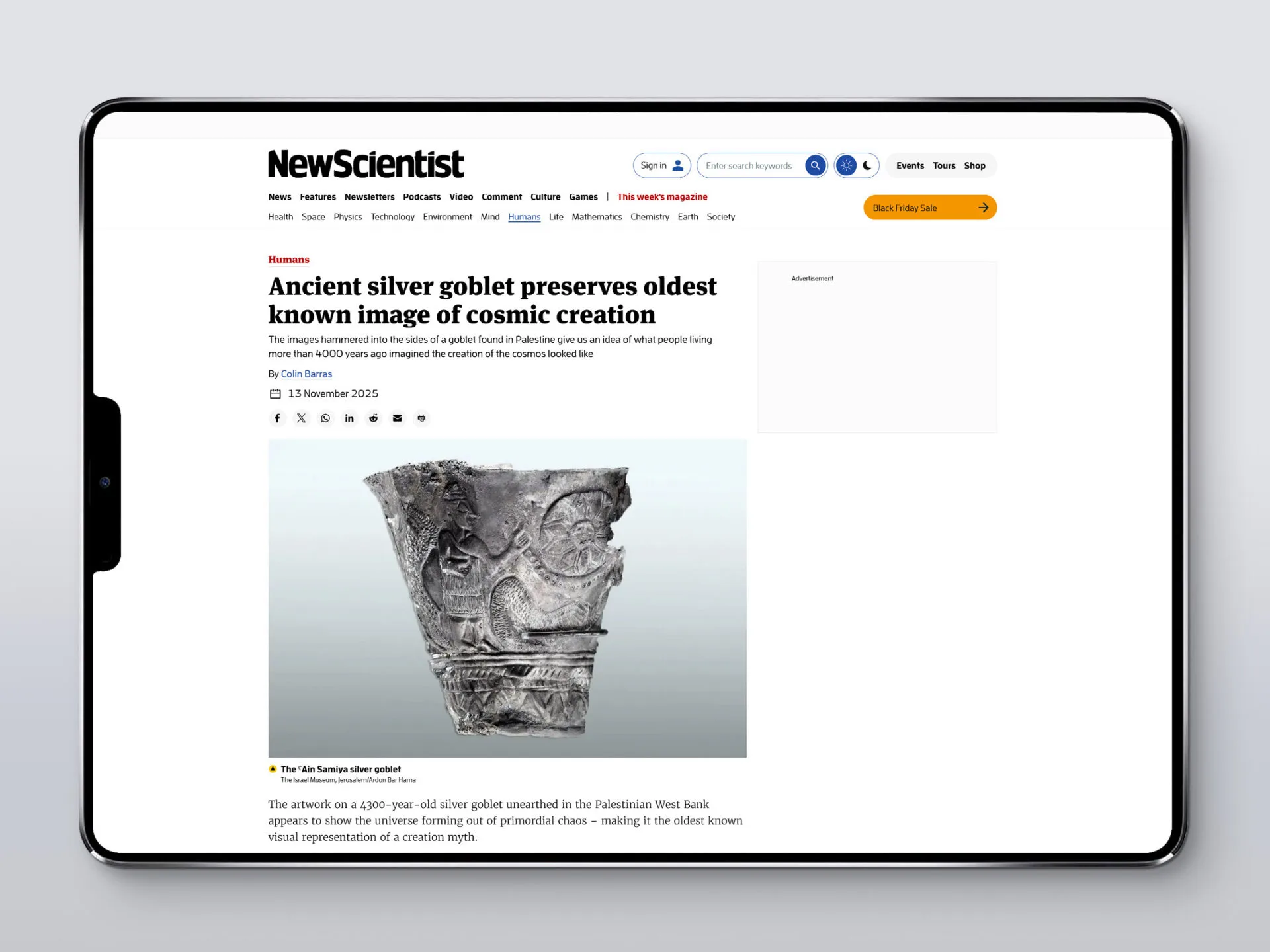

Three articles on the reinterpretation of the decorations on the 4,300-year-old silver goblet from ˁAin Samiya – and their implications for understanding cosmological concepts in

Your generous donations enable us to continue our in-depth research and share the story of the Luwian civilization. Help us to shed light on this important chapter of ancient history – with your donation or by actively participating in our research and educational projects.

GET INVOLVED