The sequence of events presented here follows the model of Late Bronze Age collapse developed by Eberhard Zangger in his 1994 book Ein neuer Kampf um Troia (A New Battle for Troy).

Until around 1250 BCE, the cultures of the eastern Mediterranean flourished. These included the New Kingdom of Egypt, the Mycenaean petty kingdoms in southern Greece, and the Hittite kingdom in central Anatolia. An extensive trade network enabled the exchange of raw materials and high-quality goods over thousands of kilometers. Writing systems served primarily administrative purposes but were also used to record rituals and festive events. Among the most significant events of this era were the Battle of Kadesh between the Hittites and Egyptians in 1275 BCE and the subsequent peace treaty of 1258 BCE, which is considered the oldest known written state treaty. Around 1250 BCE, Mycenaean culture reached its peak. During this period, the monumental citadels of Mycenae and Tiryns were constructed.

Around 1230 BCE, the Hittite kingdom was the dominant power in the northeastern Mediterranean. However, internal conflicts and external threats increasingly took their toll on the realm. The royal family in Hattuša was weakened by dynastic disputes. At the same time, elements of Luwian culture, which shaped western and southern Anatolia, gained influence even in the Hittite core areas – reaching as far as the capital. Neighboring states consistently exploited this weakness. In the west, former vassals gradually broke away from the central power and apparently even formed an alliance. In the east, Assyrian troops advanced and secured the strategically important ore mines of Išuwa. In the north, the Kaska, who had long posed a threat and controlled access to the Black Sea, grew stronger. In the south, Tarhuntašša, previously a loyal vassal state, broke away from Hattuša. Only Syria, ruled by a branch of the Hittite royal family, remained loyal to the empire. Yet the Hittites’ hegemony over Asia Minor could no longer be maintained. The decline had begun.

Relatively little is known about the situation in western Asia Minor. With the exception of Troy, there have been hardly any systematic, large-scale excavations of Late Bronze Age settlements – although around 500 larger sites from the second millennium BCE have now been identified. Many of these settlements reached diameters of over 500 meters and were inhabited for centuries. Nevertheless, we still know surprisingly little about the culture of their inhabitants.

In recent decades, numerous theories have been developed to explain the collapse of Bronze Age cultures. The causal chain presented here begins with the loss of the copper mines of Išuwa in eastern Asia Minor, which Assyria wrested from the Hittite kingdom. To compensate for this economic loss, Great King Tuthalija IV annexed Cyprus, a key supplier of copper. There, he had military bases built and thereafter levied taxes on goods handled in Cypriot ports. This measure is likely to have met with resistance from the Aegean coastal states, as they were accustomed to free access to these ports. This significantly exacerbated tensions in the eastern Mediterranean.

Shortly after 1200 BCE, the heyday of Late Bronze Age cultures came to an end within a few decades. Egyptian temple inscriptions tell of invasions by ethnically heterogeneous but apparently coordinated groups who appeared unexpectedly on the coasts of the eastern Mediterranean in fast ships, plundering and destroying port cities. This alliance is known today by the collective term “Sea Peoples.” According to traditional sources, the attackers can be linked primarily to small states in Western Asia Minor; regions such as Libya, Crete, and Sardinia have also been suggested.

A remarkable testimony to these events can be found in the Archaeological Museum of Nicosia in Cyprus: a fist-sized clay tablet inscribed in Cypriot script (Enkomi 1687). According to the Dutch ancient historian Fred Woudhuizen, it contains the report of a Cypriot admiral who, around 1192 BCE, encountered a large fleet of warships while on patrol in the Aegean Sea. The ships had set sail from Troy and were under the command of a Trojan prince named Akamas. Faced with superior forces, the admiral withdrew and headed for the safe harbor of Limyra on the southwestern Anatolian coast. From there, he warned his king in Cyprus and requested reinforcements. If this interpretation is correct, it would constitute the earliest documented sighting of a Sea Peoples fleet. This dramatic scene is depicted in the key visual of the section “Why the Luwians Are Important Today.”

Egyptian sources describe the so-called “Sea Peoples” as coming from the Aegean region; their presence is also documented off the Lycian coast. One possible aim of their campaigns was to liberate Cyprus from Hittite control.

The largest Luwian hieroglyphic inscription from the Bronze Age, carved on the Nişantaş rock in Hattuša, recounts how the last Hittite Great King Šuppiluliuma II fought for supremacy over Cyprus in naval battles. It is remarkable that the text remained unfinished. Shortly thereafter, Hattuša was abandoned. After the conquest of Cyprus, the attacks along the Levantine coast seem to have continued. Ugarit, a central trading center for exchange with Mesopotamia, was destroyed. A letter (RS 18.147) from the last Bronze Age king of Ugarit, Hammurabi, describes the dramatic situation and asks the king of Cyprus for help:

”My father, behold, the ships of the enemy have come here; my cities have been burned, and they have done evil in my land. Does my father not know that all my troops and chariots are in the land of Hatti and all my ships are in the land of Lukka? So the land is left to its own devices. May my father know: the seven ships of the enemy that came here have done us much harm.”

The letter was discovered during excavations in Ugarit – indicating that it had never left the city. Ugarit, too, fell victim to the destruction.

There are no written records for the period immediately following these events. If we compare the Egyptian inscriptions of Medinet Habu with the contingent lists handed down in the Iliad, we obtain at least a hypothetical picture of a temporary shift in power: from northern Greece across large parts of Asia Minor to the southern Levant, the attacking alliances may have gained the upper hand for a few years.

The next phase of upheaval followed a few years after the Sea Peoples invasions and is summarized under the modern collective term “Trojan War.” However, this does not refer to the 51-day siege described in the Iliad, but rather to the chain of events that can be reconstructed from various ancient traditions and that Homer condensed into literary form. According to tradition, the Mycenaean petty kingdoms mentioned in the Catalogue of Ships in the Iliad formed an alliance and carried out military operations against the coasts of Western Asia Minor – that is, against the regions from which parts of the Sea Peoples had previously been recruited.

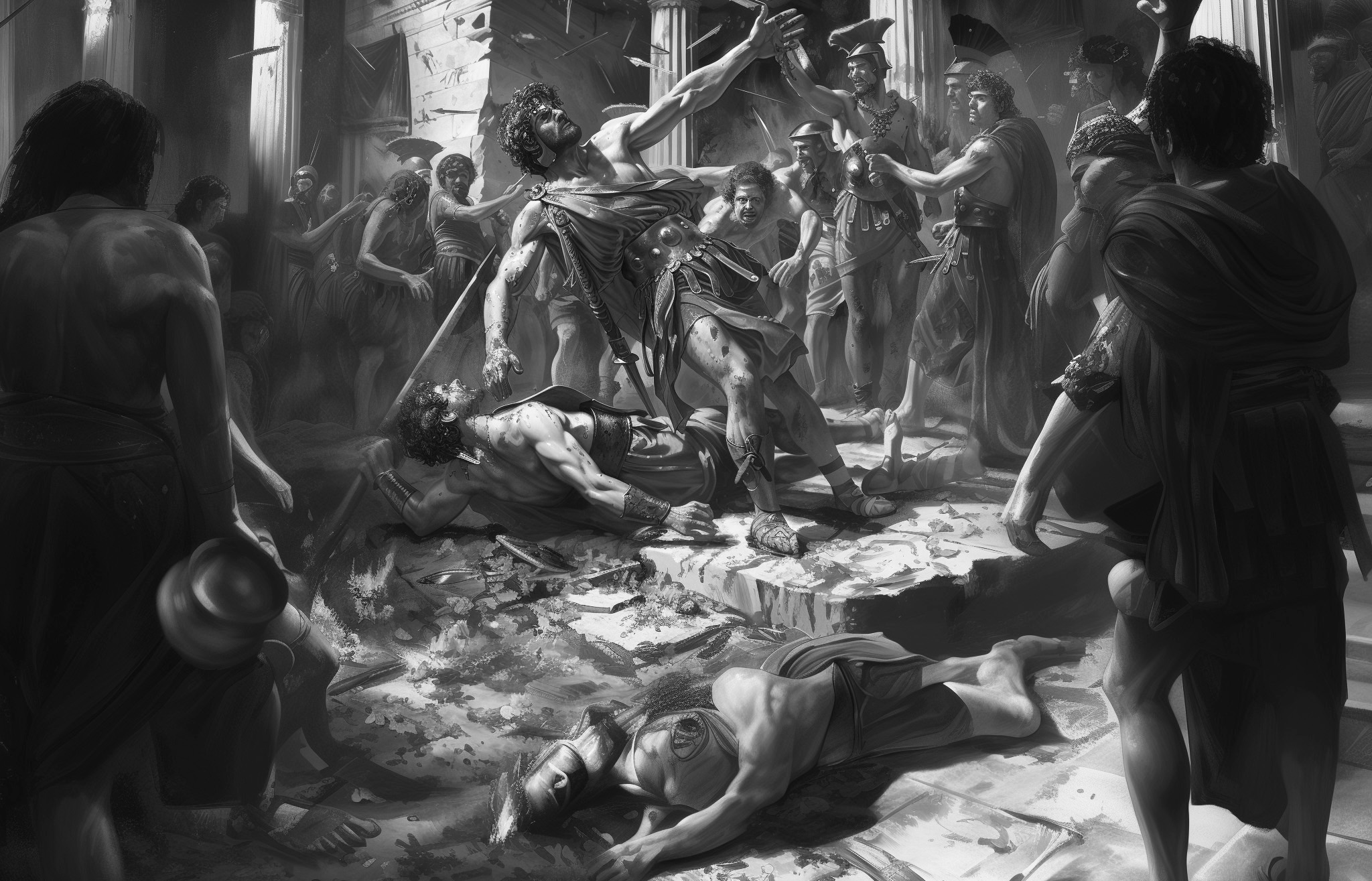

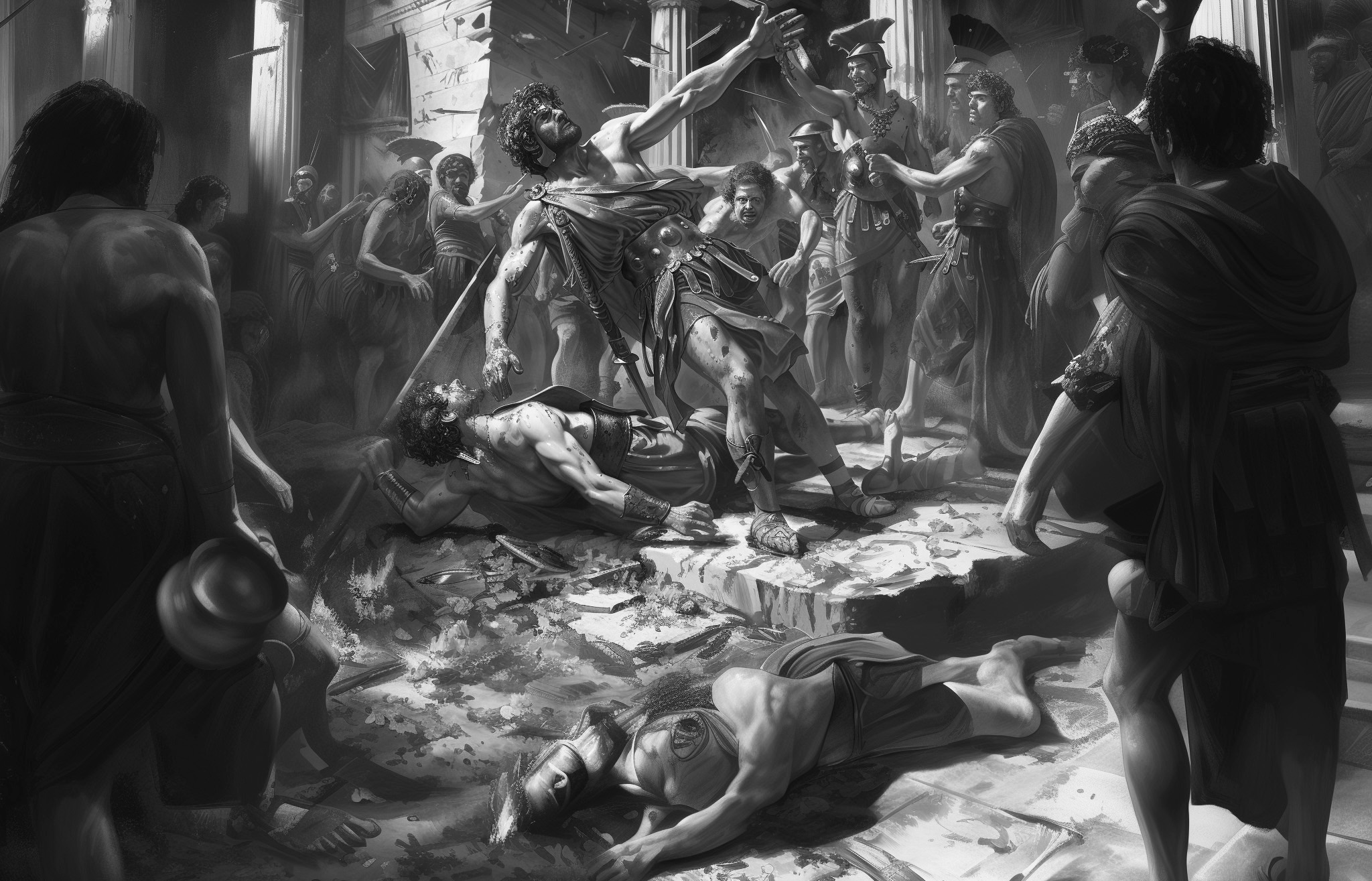

One possible explanation is that the Mycenaean rulers, who had not been directly involved before, found themselves confronted with a new territorial power constellation after the Sea Peoples' invasions that controlled both sources of raw materials and trade routes by land and sea. In order to break this dominance, they may have adopted a coordinated approach modeled on that of their opponents. The newly formed alliance in Western Asia Minor was apparently unable to defend both the territory it had gained in the east and its own coastal cities in the Aegean. Thus, the Mycenaean attackers succeeded in conquering dozens of coastal cities and advancing as far as Troy. According to later tradition, a decisive confrontation took place there. Non-Homeric sources report that the city ultimately fell due to betrayal: a gate was left unlocked at night, possibly as a result of bribery.

With the fall of Troy, the Western Asian alliance system also collapsed. It lost its importance just as quickly as the Hittite Empire had before it.

The Mycenaean rulers of southern Greece initially emerged victorious from the conflicts. However, success came at a high price. Many members of the elite had fallen in the wars, and power vacuums arose in their home regions. Deputies who had ruled during the campaigns were not always willing to cede power to the returning kings. This led to internal conflicts, uprisings, and violent power struggles. One kingdom after another fell into instability. Archaeological findings show that the destruction in Greece spread from east to west in stages; Pylos and Ithaca seem to have been among the last centers to be affected.

The Odyssey preserves a literary memory of this phase of uncertainty: at the court of Ithaca, numerous suitors court Penelope and indirectly claim the succession of the absent Odysseus. Even if the text is not a historical account, it clearly reflects a period of political tension and competing claims to power.

Three successive phases of war can be distinguished: first, the invasions by the Sea Peoples; then the Greek counterattacks summarized as the Trojan War; and finally internal conflicts in Greece. A recurring pattern is striking: although the attackers came from the west in each case, the large-scale destruction began in the east and spread from there to the west. This sequence paints a picture of a complex collapse – the first documented end of a widely networked Bronze Age world.

After the destruction of the late second millennium BCE had subsided, it became clear which regions had been particularly hard hit – and which were reforming. The former center of power, Hattuša, had fallen. Its political role was initially assumed by Gordion, the capital of the Phrygian kingdom, and later by Sardis, the center of the Lydian realm. Benefiting from rich mineral resources, fertile soils, and control of important trade routes, Asia Minor was able to recover economically and prosper once again.

Greece, by contrast, underwent several centuries of profound upheaval. Archaeological findings point to a decline in complex political structures and a prolonged loss of literacy. This era is often referred to as the “Dark Age.”

At the same time, new cultural dynamics emerged in the Mediterranean region. The Phoenicians established an extensive trade network connecting large parts of the Mediterranean. The Etruscans established themselves in northern Italy. Both cultures show parallels to the traditions of Western Asia Minor in certain respects, which could indicate processes of cultural transfer in the wake of migration movements following the crisis years.

Greek settlers began to establish themselves in Asia Minor and absorb the cultural influences there. In fact, many of the pre-Socratic thinkers – including Thales, Anaximander, and Heraclitus – were born in Western Asia Minor. This underscores the continuing cultural significance of Anatolia for the intellectual development of the Greek world.

In ancient Greece, the memory of the heroic age and its demise remained alive for centuries. Many traditions were preserved in the so-called Epic Cycle, from which Homer also drew his material. In addition, the monumental walls and remains of Mycenaean hydraulic structures remained visible in the landscape for a long time, serving as evidence of a bygone era.

In classical antiquity, numerous Greek authors attributed the end of the heroic age to “the Trojan War.” This term, however, apparently referred less to a single battle – as described in the Iliad – than to the complex series of conflicts during the crisis years around 1200 BCE.

It is noteworthy that for many centuries sympathies often lay with the Trojans. European ruling houses – from Julius Caesar to the late Middle Ages – traced their ancestry back to Trojan forefathers in order to enhance their legitimacy. It was not until modern times that the perception of Troy changed dramatically. With changing historical and political interpretative frameworks, the Trojan tradition lost its symbolic significance in Western Europe. The extensive excavations led by Heinrich Schliemann in the nineteenth century brought Troy back into the public eye but revealed a settlement that had been destroyed many times and did not correspond to the monumental metropolis suggested by earlier literary traditions.